Creating Coalitions to End Extreme Sentencing for Women

On September 24 and 25, the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide, the National Black Women’s Justice Institute, The Sentencing Project, and Harm Reduction International hosted a convening entitled “Creating Coalitions to End Extreme Sentencing for Women.” The event was the third Alice Project convening, and the first that focused on the United States.

The Convening brought together over 50 leaders in the fields of women’s rights, criminal system reform, and death penalty abolition for a strategic conversation about women facing extreme sentences in the United States. Over the course of two days, participants met in full-group plenaries and broke off into smaller discussion groups.

The Convening revealed a glaring need and hunger for collaborative work to end the extreme sentencing of women. Participants discussed how this movement will support healing-centered justice by focusing on the experiences of women. Participants also emphasized the importance of creating coalitions and centering the voices and leadership of the women directly affected by extreme sentences.

Women and healing-centered justice

The Convening opened with a discussion about how, by focusing on the extreme sentencing of women, this movement will challenge the punishment paradigm that currently dominates society’s response to harm. Despite the common misconception that “death is different,” the entire punishment paradigm, not only capital punishment, is extreme and ineffective. For example, life without parole (LWOP), which is often considered an acceptable alternative to the death penalty, also violates human rights and dignity. Convening participants emphasized the importance of rejecting not only capital sentencing, but all forms of extreme punishment.

This punishment paradigm affects the lives of people of all genders. However, the experiences of women, who make up a relatively small proportion of prisoners, are often minimized or ignored. Convening participants discussed how they can unite to fight the societal inclination to dismiss the experiences of women serving extreme sentences.

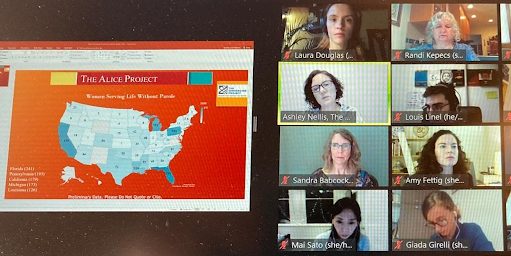

Participants discuss a map displaying the number of women serving LWOP around the country.

The complex stories of individual women challenge the punishment paradigm. Women’s stories demonstrate how harm is rooted in structural violence, and how structural inequities both put people at risk of being harmed and causing harm. Women’s stories also challenge the dichotomy between victims and perpetrators. Many women involved in the criminal justice system, for example, are victims of abuse or sexual violence. By focusing on women, the movement encourages a new societal response to harms, one that has healing, rather than punishment, at its center.

Coalition-building

Participants expressed that divisions between communities impede the movement to end extreme sentencing for women. The criminal justice reform community has collaborated little with the gender justice community, and, even within the criminal justice field, the death penalty abolitionist community has been largely divided from larger criminal justice reform efforts. Further, barriers often divide lawyers, academics, advocates, and community members.

These divisions prevent cooperation and resource-sharing, and result in conflicting strategies. For example, some death penalty abolitionists advocate for LWOP as an alternative to the death penalty, which impedes other groups’ efforts to abolish LWOP. These communities, however, share the same end goals and would benefit from collaborating.

The Convening was a prime example of how collaboration between communities can spark new ideas. The Convening brought together researchers, attorneys, journalists, and advocates from feminist, sentencing reform, and death penalty abolitionist communities. Attendees hailed from a wide range of organizations, including the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, the Women’s Prison Association, Reprieve U.S., the Death Penalty Information Center, The Sunny Center, the Open Society Foundations, Survived & Punished, Witness to Innocence, the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty, Impact Justice, the 8th Amendment Project, and the Abolitionist Law Center. These organizations and individuals each brought their own expertise and perspectives to the discussion. Participants learned about one another’s work, shared resources, and identified opportunities for collaboration.

Convening participants discussed how they can continue to break down barriers within the movement. Participants suggested dozens of additional organizations that should join the collaborative network, and brainstormed how to connect with other fields such as the anti-violence community. Some participants also emphasized that the legal community should increase its cooperation with community organizations so that the community can provide alternative narratives and vital support to people involved in the criminal justice system.

Centering the voices of women with lived experience

Convening participants emphasized that the movement must center the voices and leadership of the women directly impacted by extreme sentencing. During the Convening, several women described their personal experiences of receiving extreme sentences. They explained how the prosecution used gender stereotypes to attack their character and demean their roles as wives or mothers. They told how their attorneys worsened the injustice by failing to present an adequate defense. They described horrific prison conditions and the isolating and overwhelming experiences of incarceration. The humiliating treatment inflicted by corrections officials, they explained, was often even more difficult to endure than the physical conditions of confinement. They survived years of solitary confinement, deprived of contact with their children and families. The speakers identified numerous gender-based abuses, including sexual assault and an absence of doctors who understood women’s mental healthcare needs.

Participants listen to Sunny Jacobs describe her experience of serving an extreme sentence.

These women also identified several important priorities for the movement. They emphasized that outside emotional support is one of incarcerated women’s most vital needs. Outside support, such as letters or phone calls, reminds women that people on the outside have not forgotten about them. It helps them maintain hope and fight feelings of isolation. Some women also said that the foremost concern for many incarcerated women is their families, and that supporting women’s families can help sustain incarcerated women’s emotional wellbeing. The women also mentioned that women on the inside need materials such as sanitary and medical equipment. Additionally, they pointed out, women on the outside need access to services that help them avoid situations that put them at risk for incarceration.

These women also explained how they are working with other advocates, many of whom also have lived experiences, to fight against extreme sentencing for women. They lead and participate in organizations that support women on the inside and advocate to change the punishment paradigm. They are also sharing their stories with people on the outside. These women agreed that sharing and reliving their experiences is not easy, but said they believe that the pain of re-traumatization is worth the opportunity to change the system for future women.

Sunny Jacobs speaks during the Convening.

Next steps

The insights and stories shared by women with lived experience provided one of the highlights of the convening. Many convening participants emphasized that the movement must prioritize the urgent needs that the women identified and, in the future, continue to center the voices of women with lived experience. Participants also talked about how they can create and support platforms for women with lived experiences to share their stories. To foster self-care within the movement, participants suggested story-sharing formats such as documentaries that would allow women to share their experiences widely without repeatedly enduring re-traumatization.

The participants also discussed other next steps for the movement. Several people mentioned the importance of advocating for all women. The movement should not focus its advocacy on groups who tend to attract more public support, such as women who are factually innocent or who have experienced domestic violence, and ignore the larger population. Participants also emphasized that, while working towards the movement’s long-term goals, advocates cannot forget immediate needs. The movement should dedicate time and resources to the women who are suffering from extreme sentences now. Additionally, the movement must increase its attention towards trans and gender non-conforming individuals, who face unique challenges but are often excluded from the discussion. Participants also expressed a need for research because a lack of data impedes advocacy. To translate goals into action, participants are collaborating on a list of concrete next steps and a research agenda.

The current moment demands action. Recent protests have opened up the public discussion about systemic inequalities in the criminal legal system, and the #metoo movement has revealed the prevalence of sexual violence and its devastating consequences on survivors. Participants suggested that the movement should prioritize outward-facing work to seize this moment of public awareness.

This conversation will not be the last. The Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide and its partner organizations will continue to build coalitions across fields and communities, share resources, and create spaces to continue discussions. This convening was merely a first step toward building a powerful, inclusive movement to end extreme sentencing for women.

The recording of the panel of women with lived experiences is available below: